A brief look at the Assyrian cassette culture and its demise.

In the 1980s, Iraqi television had only two channels dedicated to the Arab state and culture, while the Assyrian language was not permitted on TV or radio, so cassettes became the only source to distribute our popular culture, entertainment, and, at times, national education.

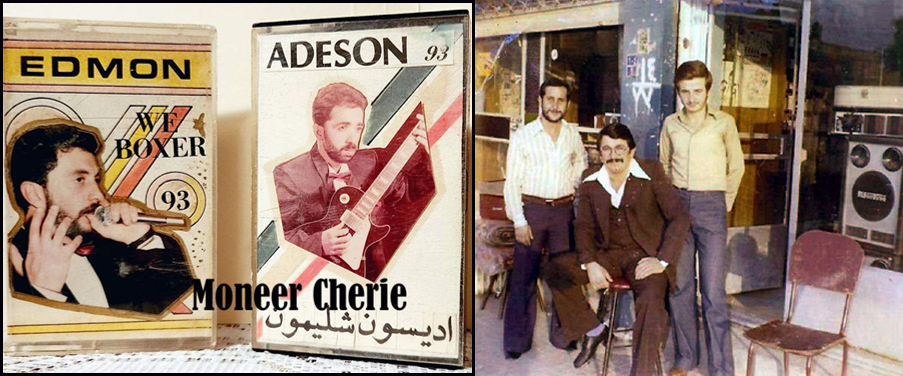

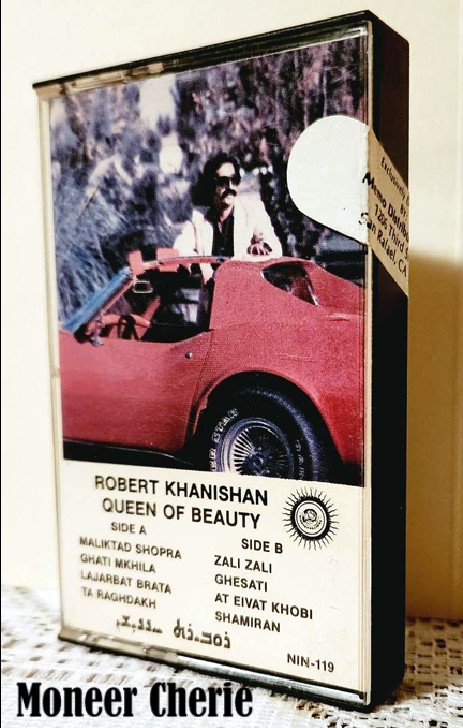

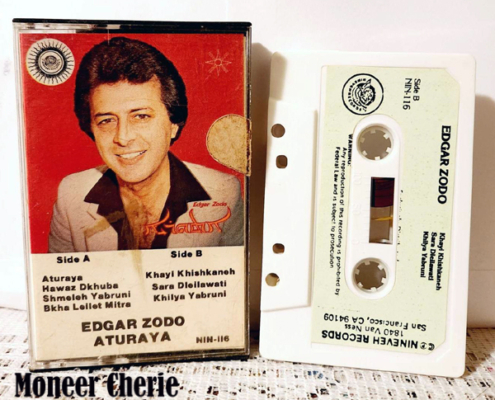

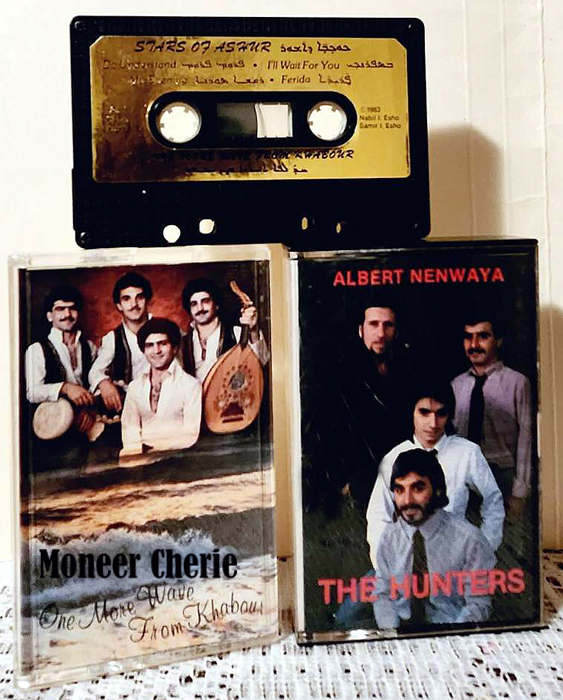

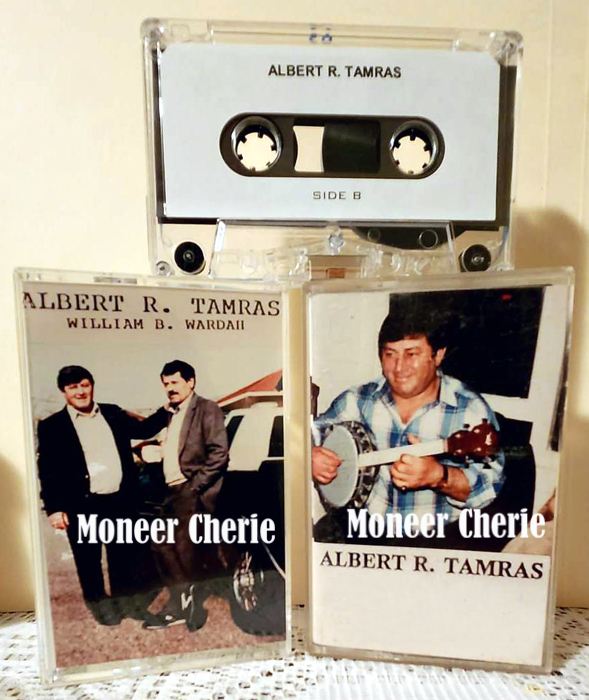

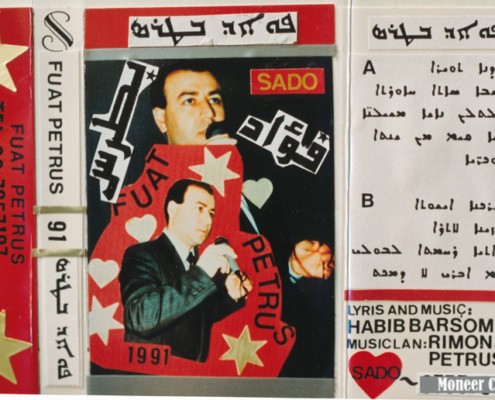

The majority of Assyrian tapes were produced in the United States and Europe. But a small number, which are more difficult to find, were produced locally at the grassroots level, by people who recorded music in their communities, at private parties, weddings, or by local bands. The only source of semi-official productions were released by a few privately run music stores in Baghdad, like Al-Baraq, Hamurabi, and Oscar.

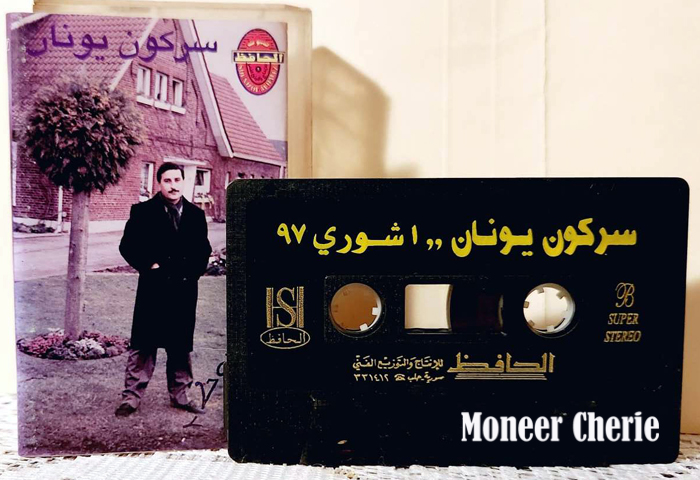

Since most Assyrian tapes in the Middle East were bootlegs, obtaining the original Assyrian cassettes at that time was nearly impossible, and if you had managed to do so, you quickly became popular among your friends, and that only happened if you had a cousin visiting from overseas who was able to smuggle in one or two cassettes without them being confiscated at the border, since the Iraqi government had banned most Assyrian singers.

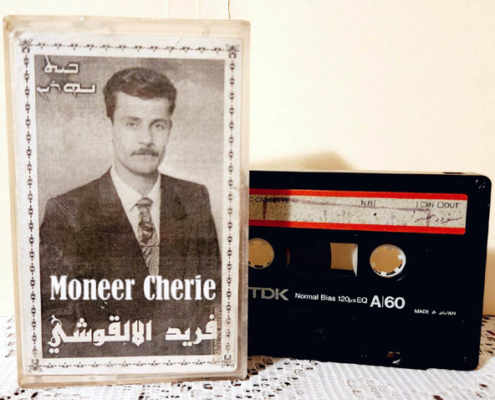

On numerous occasions, you would purchase a new cassette album of a specific singer from your local music store, only to discover later that the songs on the tape actually belonged to a different singer, and this was apparently done to either avoid problems with the authorities by selling a banned singer, or simply because the music store owner made a mistake because probably all he got was a bootleg copy with no details of the singer.

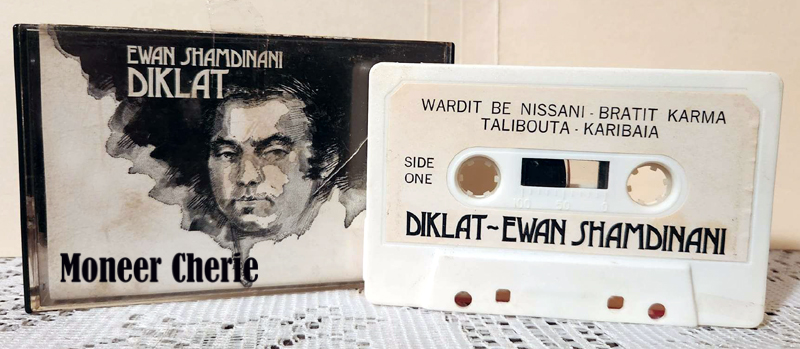

Almost every Assyrian home in the 1980s had a small collection of Assyrian cassettes, and some guys would display their collection very proudly, especially if they had managed to locate official album sleeves, which most of the time were no more than xerox bootleg copies.

And we quickly learned one thing; never lend your original tape to anyone, especially if the cassette shells are the screwed-on type and not welded. Because the borrower had the ability to swap out your original reels for a copy and screw back the tape shells without your knowledge.

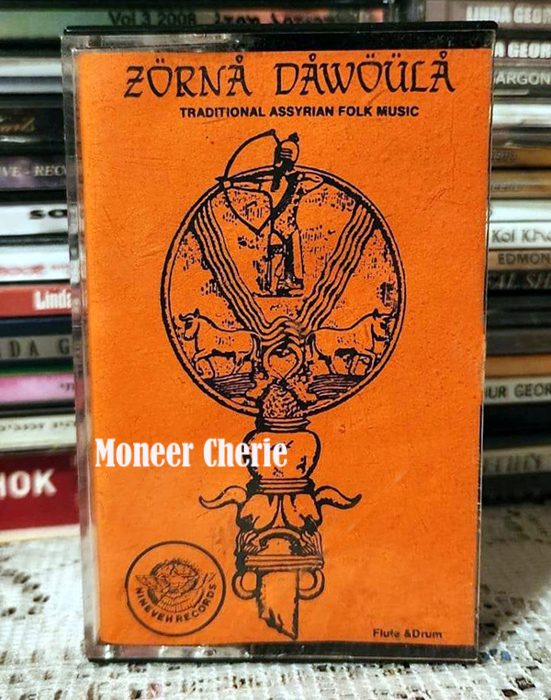

Unlike vinyl records, cassette technology made it easier to produce and distribute Assyrian music worldwide because it was less expensive, easy to duplicate, and durable. It made it easier for Assyrian musicians to create a mini-boom in the music industry, which in the 1980s and early 1990s became known as the “golden age of Assyrian music.”

I have been collecting all formats of Assyrian albums for nearly fifteen years, and a large part of that collection has been tapes. On a couple of my overseas trips, I was lucky enough to still find vintage Assyrian cassettes that had survived the country’s many wars and devastation. I remember meeting a music store owner who had moved his entire stock from Baghdad to Erbil.

At the front of his shop, he was only selling CDs, but when I asked him if he had any cassettes? I could tell he was surprised that a customer in 2016 was asking for tapes, so I asked if I could check them out and told him I would be buying, so he knew I wouldn’t be wasting his time, and he agreed to let me into his storage. All I saw were stacks of tapes on shelves all the way to the ceiling and a few tapes still in their moving boxes.

Of course, he not only had Assyrian tapes but also Arabic and Kurdish; however, I was only interested in Assyrian tapes, and it took me a couple of visits to ensure I didn’t miss any interesting Assyrian tapes in his collection. The stench of rat urine and thick layers of dust in the old storage didn’t deter me from my arduous search for any elusive tape. I came away with nearly 30 tapes, mostly domestically produced original Assyrian tapes.

When I first traveled to Erbil in 2016, there were over ten music stores selling mostly CDs and digital music, but years later, when I returned, only one had remained open; most had been forced to shut down because of the economic downfall and digital music downloads online.

(On one of my previous trips to Iraq, standing next to a music store that is no longer in business)

(On one of my previous trips to Iraq, standing next to a music store that is no longer in business)

But unfortunately, I wasn’t always able to get access to known collectors and their collections. When I visited a famous collector in Iran, he told me that he was busy and couldn’t make more time for me to check out his collection, so I only managed to take a few photos. He told me I should come back later that week, but I was leaving the same week and never had the time to go back and check out his collection. Other collectors from around the world are either unfamiliar with how to digitize their collections or are unwilling to share what they have collected.

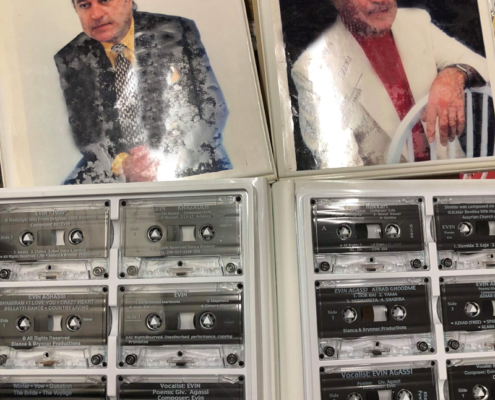

(Two sets of Evin Agassi cassettes were reissued in the 1995)

I noticed that Assyrians were the fastest to adopt digital formats. I saw customers in Iraq walking into music stores with a blank memory stick, filling it with the latest albums in digital format, paying, and walking out. Of course, most of the music on Assyrian tapes has made the jump to digital formats. but not everything, especially those songs that were never issued on tapes in the first place, especially those made for Assyrian radio segments in Iran and Iraq in the mid-1960s to the beginning of the 1970s.

Nowadays, almost no one owns cassette tapes, and the vanishing music stores are a warning sign of the end of physical copies. What remains is mostly in the hands of collectors or kept by a few people for nostalgic reasons. And these surviving tapes are now a passage into an irretrievable time and space in Assyrian popular culture.

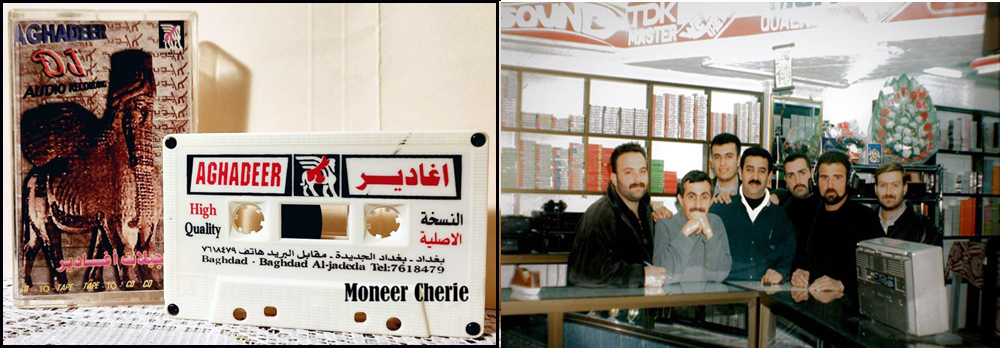

Al-Baraq Record Store on Al-Sina’a Street, Baghdad in 1979, with owner Mr. Saib Habbaba seated.

Mr. Zaya Shiba owner of Marco Record Store in Nuhadra, Iraq. store is no longer in business.

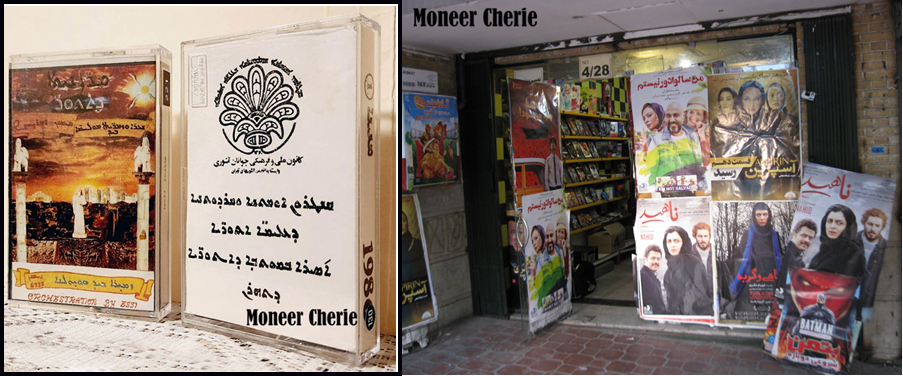

The shop front of an Assyrian owned Music Store in Tehran Iran in 2016

Aghadeer Music Store (2nd Branch) in Baghdad around 1996

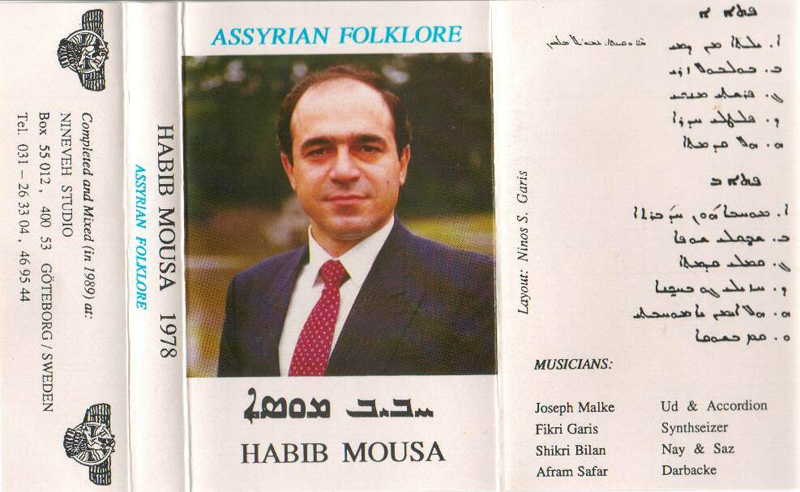

Habib Mousa – Assyrian Folklore Songs, released in 1978

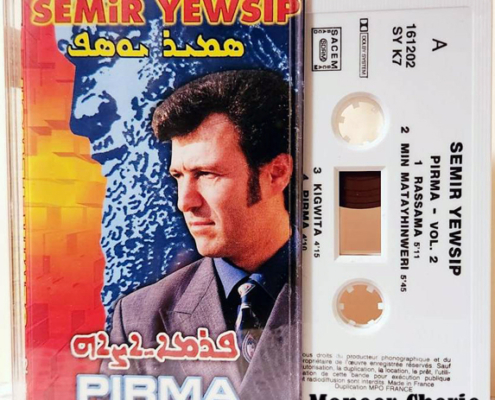

Semir Yewsip – Pirma, released in 2003

Semir Yewsip – Pirma, released in 2003

Three versions of the same album released by Linda George in 1983

Three versions of the same album released by Linda George in 1983

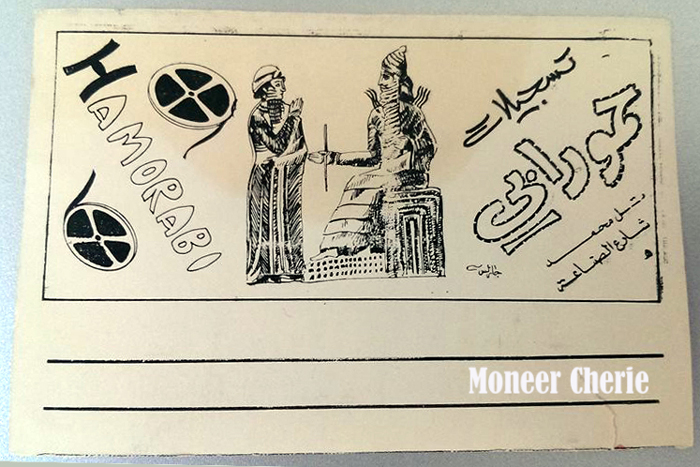

Cassette Sleeve from the old Hamorabi Music Store in Baghdad.

Cassette Sleeve from the old Hamorabi Music Store in Baghdad.

With Mr. Calvin at the Hamurabi Music Store in Erbil, Iraq, one of the last remaining Assyrian music shops in Ankawa.

With Mr. Calvin at the Hamurabi Music Store in Erbil, Iraq, one of the last remaining Assyrian music shops in Ankawa.

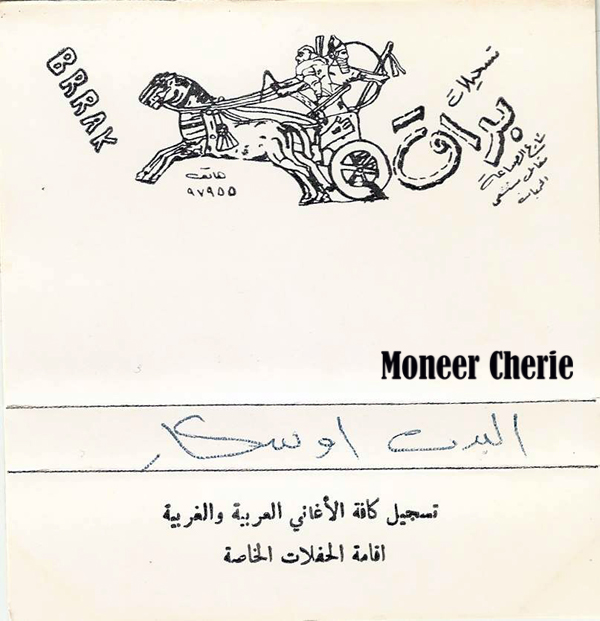

Original Tape Sleeve from Al-Baraq Record Store, Baghdad.

Original Tape Sleeve from Al-Baraq Record Store, Baghdad.

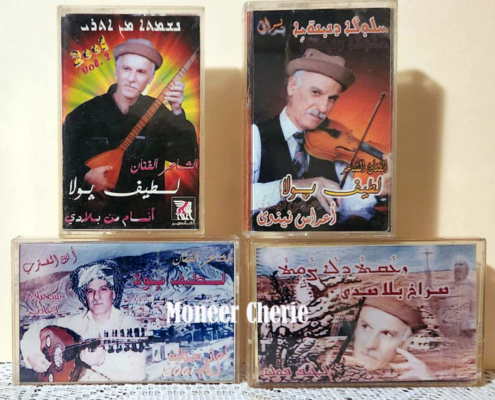

Selection of Latif Pola Cassettes

Selection of Latif Pola Cassettes

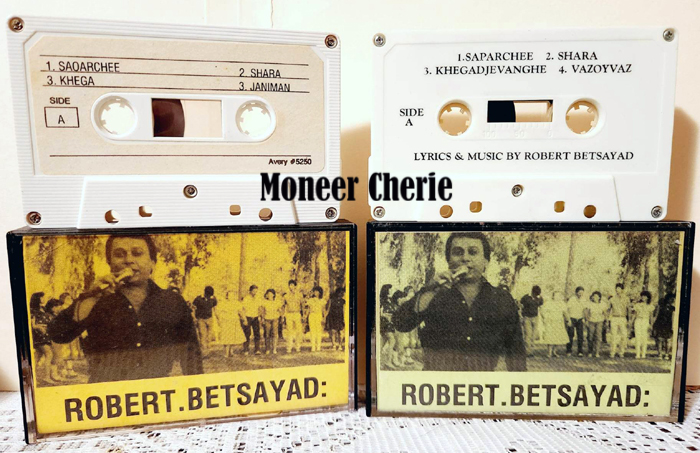

Two different pressings of the same tape by Robert Bet Sayad, 1986

Two different pressings of the same tape by Robert Bet Sayad, 1986

Two different pressings of the same tape by Geliana Esho, 1988

Two different pressings of the same tape by Geliana Esho, 1988

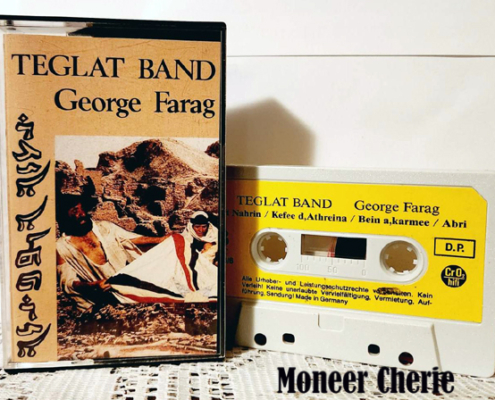

George Farag (with Teglat Band) – Bet Nahrain – 1982

George Farag (with Teglat Band) – Bet Nahrain – 1982

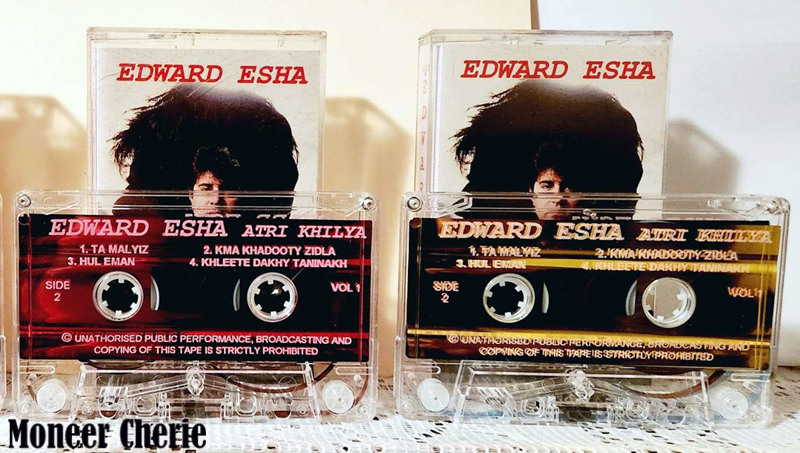

Edward Esha Tape in two different color “slip sheet”, released in 1993

Edward Esha Tape in two different color “slip sheet”, released in 1993

The (Voice of Nineveh), was one of the best Assyrian music stores in Iran

The (Voice of Nineveh), was one of the best Assyrian music stores in Iran

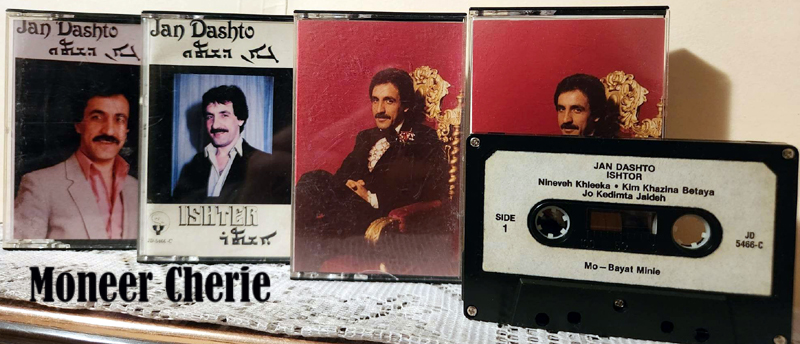

Same album by John Dashto in four different pressings 1982

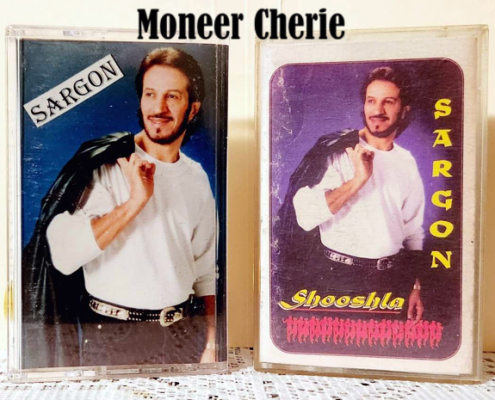

The same Sargon Gabriel album was released in 1996, with one copy in America and the other in Australia.

The same Sargon Gabriel album was released in 1996, with one copy in America and the other in Australia.